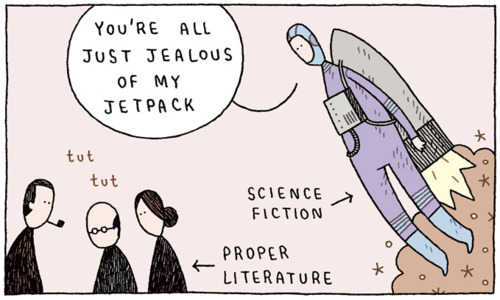

Maybe this kicking cartoon by Tom Gauld sums up what is going on here? Check out more of Tom's cartoons on his website (and buy his books).

So Laura Miller, co-founder of Salon.com and one of the most famous literary critics of our day, jumped back into the genre pool with the essay "Dark Futures: What happens when literary novelists experiment with science fiction."

To summarize, in the essay Miller tracks all the "literary" authors who are now writing science fiction. According to Miller these authors are writing SF because it's so hard to write contemporary fiction with the world constantly changing. So why not write SF instead? She then name checks the authors doing so, including Emily St. John Mandel and her best-selling novel Station Eleven, which Miller notes the author doesn't even consider SF.

Why that author's disavowal? Oh, because as Miller says "Science fiction writers and readers have long resented incursions like these into their territory, especially when they come, as such novels often do, with a disavowal of the genre itself."

In case you can't tell, Miller's words are an irritating excuse for an essay, with the irritation building like a flea circus loose under a wool sweater until the reader breaks out in a never-ending rash. Only then does Miller close with a grasp at profundity by saying "What’s surprising is not that literary novelists are increasingly taking up science fiction’s tools, but that more of them didn’t try it sooner."

So. Much. Fail. In. One. Essay. And before you believe I'm biased because I'm one of those lowly SF authors who need step aside for my literary betters, check out the reaction of other authors to Miller's words:

- English author Joanne Harris, known for many award-winning novels including Chocolat, said she wanted to flip her table at Miller's comment that the "specialty of literary novelists (is) the fullest appreciation of humanity in its infinite variety and intricacy."

- Critic and author Damien Walter said "It's a bad essay, more for not recognising that fantasy, imagination and myth existed as part of literature before the SF genre was born."

- After reading the essay SF author Alex Acks added "Apparently none of us can write a character to save our lives."

- Author Felicia C. Sullivan said about the essay that "Lit fiction authors are often the most irritating. SF is hard and brilliant (with a canon) and isn't something to which a writer panders."

Part of the problem with the essay, beyond Miller's actual condescending words, is that she overlooks the ability of SF authors to write at the level of the authors she's praising. She grudgingly gives William Gibson and Karen Joy Fowler minor props but ignores the stylistic and literary ability of SF masters like Samuel R. Delany, Ursula K. Le Guin, Gene Wolfe, N. K. Jemisin, Connie Willis and so many others.

For what it's worth, Miller has long had a love-hate relationship with genre fiction. As detailed in Miller's book The Magician's Book: A Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia, she loved C.S. Lewis's stories as a child, desiring “to be carried away by something greater than ourselves — a love affair, a group, a movement, a nation, a faith. Or even a book.” But Miller fell out of love with Narnia later in life when she realized the book's Christian "legends and ideals."

I suspect this attitude carries over for Miller into all things genre. She loves the scope and vision of genre works but can't get past the imaginary blinders which to her separate genre works from what she might call "serious writings." You can see this attitude in how she describes the SF community, where she says lovers of science fiction are "both aggrieved at being marginalized and really invested in being marginalized. So they don’t really want to be accepted. They want to be angry and self-righteous about not being accepted."

As SF author Jess Hyslop said in an online discussion with me, part of the problem with this essay and overall discussions of this topic is in the use of the term "literary," as in literary fiction, literary novelist, literary writing, and so on. As Jess wrote, "Wish we could all stop using 'literary' as a (non?)genre descriptor, & instead understand it as an adjective that can apply to any genre." So true. Perhaps a better term is "contemporary fiction" or "mainstream fiction." Such phrasing would then allow anyone to apply the term literary to any writings which reach deep into the human experience and psyche.

Look, the science fiction genre and other genres such as romance, fantasy, horror, and comics are incredibly open. All are welcome to read and write within these genres. But don't come into these genres, take the best parts of what we write, then disavow the genre and everyone in it.

If you do that, all you're showcasing is your own literary ignorance.