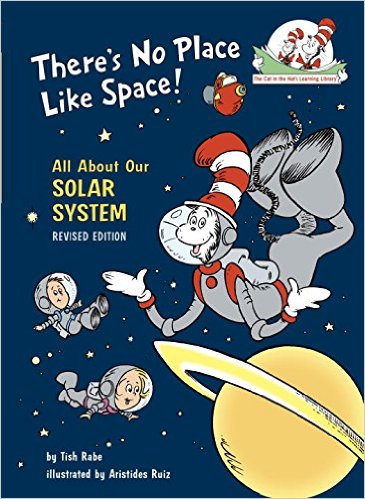

While There's No Place like Space may be great for kindergarten students, everything I really need to know I learned from the science fiction and fantasy genre.

A short essay hangs on the bulletin board in the break room at work. The essay's printed on age-brown paper and taped to a yellow sheet of construction paper, the kind kindergarten students cut with safety scissors. A totally appropriate paper choice since the essay is titled “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten.”

Written by Robert Fulghum, the essay formed the basis of his bestselling 1988 book of the same name. It’s possible the essay has been posted on my work’s bulletin board for more than a quarter century, silently offering life suggestions to impatient employees jostling for the water cooler or coffee pot.

Among Fulghum’s kindergarten suggestions are “Share everything. Play fair. Don’t hit people. Put things back where you found them. Clean up your own mess.”

It’s easy to see why an entire generation of workers kept the essay on the bulletin board. After all, it’s a nice fantasy to believe that taking a nap every day and holding hands not only makes the world a better place but keeps everyone happy.

Humans have long been attracted to basic rules of living, rules which appeal to humanity’s sense of fairness and also resonate with our cultural norms and beliefs. The most basic of these rules — commandments found in different religions such as “Thou shalt not kill” or “Do not lie” — seem obvious and easy to follow. Other rules vary across human cultures, such as norms on interpersonal contact and communications.

But even very obvious rules and norms turn out to have a lot of moral ambiguity. Every culture in the world supposedly believes that killing is wrong. Except they all have exceptions to that rule, such as allowing killing in cases of self defense. Or if you’re a soldier. Or if society decides someone should be killed. Or if the profit model of your business depends on indirectly killing people.

And rules against lying are bent even further, with very few humans being absolutely honest when describing their feelings and thoughts to other people.

Suddenly “Thou shalt not kill or lie” isn’t so “thou shalt not.” Which is how most absolute rules in life go, with the rules being good ideals but attaining more flexibility in day-to-day exchanges between people. Sometimes this flexibility is good — as in telling a white lie to spare a friend’s feelings — and sometimes it’s bad, as when the tobacco industry aggressively sells a product killing millions each year.

Maybe Fulghum’s kindergarten essay is so popular because it moves beyond the hypocrisy of how most human act with regards to rules and norms. Fulghum’s kindergarten rules take us to a supposedly simpler time in our lives. To an idealized past where all of us knew right and wrong and acted in the proper manner.

Of course, not everyone learned the same rules as a child. In my case, for example, everything I really need to know I learned from science fiction and fantasy stories.

I read SF/F stories from a young age, first in the Golden Age magazines my grandfather owned then in novels I tracked down at bookstores. I still read SF/F stories with an almost religious fever. I sometimes think reading and writing SF/F is the only thing which keeps me going. That SF/F stories give meaning to my life by showing me the deeper truths underlying our existence.

For example, from Arthur C. Clarke I learned that the ultimate destination of all humans is extinction. Even if some parts of humanity transcend reality, as in Clarke’s novel Childhood’s End, humanity as a species is destined to eventually disappear from this universe.

From Isaac Asimov I learned that even if our ultimate fate is to disappear, humanity can have an amazing ride while we exist.

From Ursula K. Le Guin I learned that culture shock can be both a way to awaken you to new intellectual horizons and to kill you.

From Octavia E. Butler I learned that we must fight to better the world, even if the fight to better the world often destroys us.

From Harlan Ellison I learned of outrage at the world as it is, even if outrage sometimes eats us alive.

From Philip K. Dick I learned to look behind the curtains of life and never be shocked by the depths to which humans go to ignore the truth about ourselves.

From Samuel R. Delany I learned that the worlds we create within ourselves can be far more amazing and unique than anything in our already amazing and unique universe.

Science fiction and fantasy stories teach us the rules for reaching beyond what humanity is at this time and place. In our hearts, humans yearn to move past what we know. We are our world’s ultimate star gazers. We want to see beyond the distant horizon, both in the physical world and in our inner, mentally created worlds.

Humans are by necessity limited in what we can do and know. Even if we experience every aspect of life out there — and even if we read SF/F stories every waking moment of our lives — there will still be countless experiences and stories we’ll never know.

But that’s okay because we exist within the location and time frame of our bodies and knowledge and beliefs. Even the most open-minded humans are unable to experience everything that is experienced by the billions of people currently living on our planet. Or the experiences of the hundred billion or more humans who have existed since the dawn of our species.

All we can do is follow our own limited paths through life. To help us travel these paths, humanity creates rules and norms and beliefs. We’re a fool to ignore these rules and norms and beliefs. We’re a fool to follow them too closely or not try to change them.

That’s one reason I love the truths I’ve learned from science fiction and fantasy stories. These truths both expand my understanding of life and ground me in the world as it exists. SF/F rules and norms are both a cry against the ultimate fate of humanity and a demand that we experience life as only we can live it.

In the end, that’s all any true SF/F lover can hope for.